IMAGE: GOPEN RAI

Nepal is better known for preserving carbon than producing it. It has projected for years the image of a low-emitting Himalayan country whose vast forests offset the greenhouse gases that development threatens to release. Since 2000 these forests have absorbed roughly 16m tonnes of carbon dioxide a year, a feat attributed in part to community-managed conservation schemes that now serve as case studies for international donors and climate NGOs. That sink, remarkably constant for over two decades, has served both as an ecological asset and a diplomatic shield. But the country beneath the tree canopy is changing.

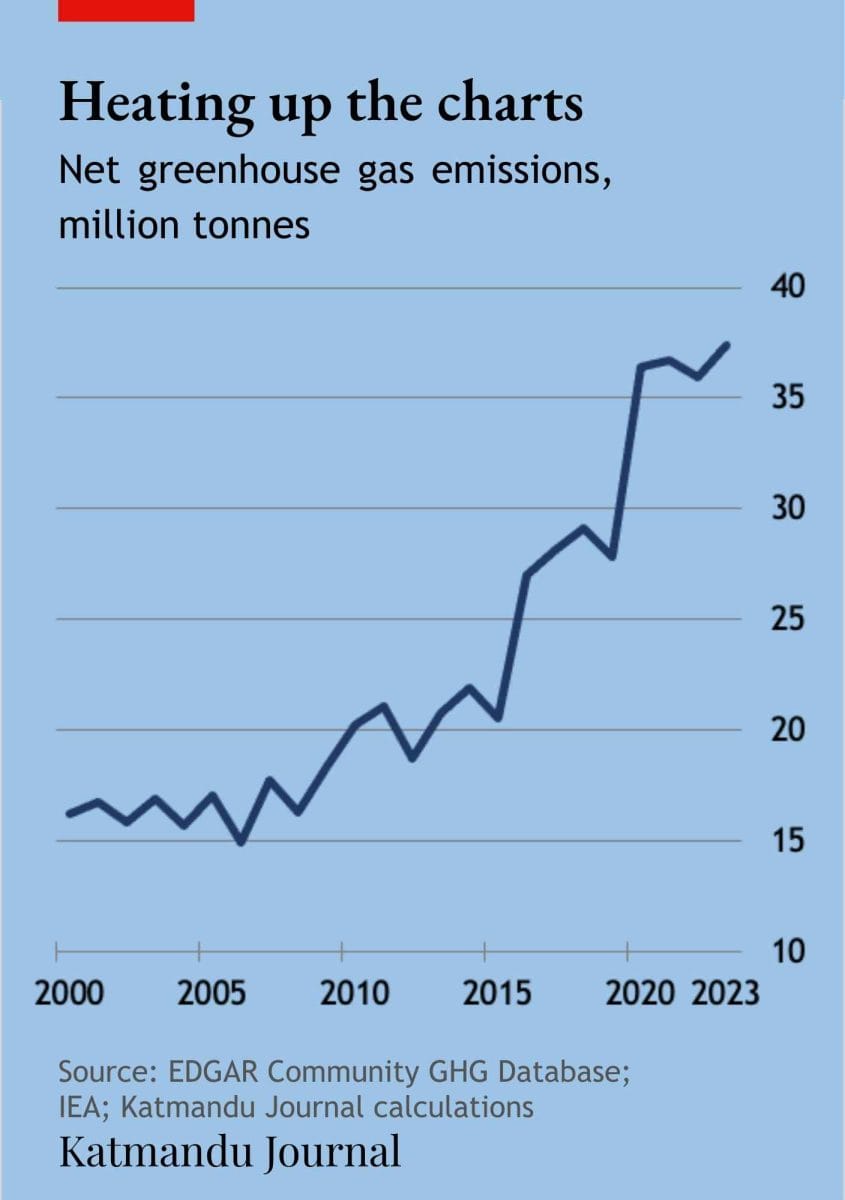

Nepal’s greenhouse gas emissions rose across all major sectors between 2000 and 2023. Carbon dioxide from industrial combustion increased more than sixfold. Transport emissions grew by nearly 475%. Methane and nitrous oxide—less visible but far more potent gases—ticked upward as agriculture intensified and waste mounted. Per capita carbon emissions, excluding land use and forestry, have more than quadrupled. Although Nepal’s absolute emissions are still small, the direction and velocity are hard to ignore.

The acceleration reflects an economic aspiration. Nepal will graduate from the UN’s least-developed country status in 2026 and has set its sights on becoming a middle-income economy. Industrial output is rising and cities are expanding, as well as consumption is growing. Those are trends consistent with the early stages of economic transformation. But they are also closely associated with rising emissions, particularly in countries where policy frameworks lag behind structural change. In Nepal’s case, the transition is not yet being managed with much attention to carbon efficiency.

No sector has expanded its emissions footprint more alarmingly than industry. In 2000 Nepal emitted just over 1m tonnes of CO₂ from industrial combustion. By 2023 that figure had hit nearly 7m tonnes. Bricks and cement account for a big share of this growth, powered largely by imported coal and diesel. Emissions dipped briefly in the early 2000s, and again around the 2015 earthquake, but the overall trend is staying sharply upward.

Hydropower, a cleaner alternative, is widely available in theory. Nepal possesses over 40,000 megawatts of economically viable hydropower potential, most of which is untapped. In reality grid reliability is patchy, investment uneven and industrial users sceptical of depending on it for base load energy. Coal, though dirtier, is more predictable.

Government strategies have not entirely ignored the problem. Various national plans, including the second Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) submitted under the Paris Agreement, have called for greater electrification and energy efficiency. Yet implementation has lagged. Industrial policy is more concerned with output than emissions.

Transport is the second-biggest source of carbon emissions in Nepal, and arguably the fastest-growing in terms of behaviour change. The number of registered vehicles has surged in the past 15 years, buoyed by rising incomes and steady inflows of remittances from abroad. Roads have expanded, though not always coherently, and the vehicle fleet is dominated by petrol-powered motorbikes and diesel-powered trucks.

Between 2008 and 2018 CO₂ emissions from transport nearly tripled. A dip in 2019 was followed by a strong rebound, taking the total to 4.76m tonnes in 2023. The government has introduced incentives for electric vehicles, including lower import duties and plans for charging infrastructure. Yet electric vehicles still account for a small fraction of the market, constrained by patchy grid coverage outside the Kathmandu Valley, among others.

Moreover Nepal’s transport network is poorly integrated, with limited public alternatives in both urban and rural areas. Fuel efficiency standards are minimal, and policy coordination between municipal authorities and national planners is thin at best.

Where Nepal’s emission story becomes more granular is in its treatment of agricultural and waste-related gases. Methane and nitrous oxide are less frequently tracked in the public discourse, but together they account for a big share of total emissions.

Methane emissions, largely from livestock and rice paddies, rose by 21% between 2000 and 2023. Nitrous oxide from agriculture—linked to fertiliser use and manure management—rose by 66% in the same period. These gases are short-lived but extremely potent.

Waste emissions, particularly methane from landfills and sewage, have also crept upward. From 0.23m tonnes of CO₂-equivalent in 2000, nitrous oxide emissions from waste reached 0.41m tonnes in 2023. The increase is small in absolute terms, but indicative of growing urbanisation and inadequate waste infrastructure.

Against this background of rising emissions, Nepal’s forests present a striking counterbalance. They have absorbed the same volume of carbon—16.23m tonnes a year—for over two decades, suggesting stability in both land use and forest health. Much of this is credited to the decentralised forestry programme, in which over 22,000 community groups manage national forest land under state oversight. This model has succeeded in reducing illegal logging, increasing biodiversity as well as embedding conservation into local politics.

Yet the apparent constancy of the carbon sink hides a more complex reality. As emissions from other sectors rise, the relative impact of the forest offset shrinks. What was once enough to balance total emissions now covers only a sliding share. There is also an upper bound to how much additional sequestration these forests can provide, especially in the absence of large-scale afforestation.

Nepal’s emissions remain low in per capita terms, at around 0.60 tonnes of CO₂ per person—well below the global average. Yet the speed of change matters more than the starting point. Emissions from sectors where mitigation is feasible, such as transport, industry, agriculture, are growing quickly, with few concrete policies in place to reverse the trend.

Critics of climate action in low-income countries argue that emissions should rise before they fall, and that growth must precede greening. Supporters of early mitigation point out that low-carbon alternatives are cheaper and more accessible than before, and that locking in dirty infrastructure today will make future transitions costlier. In Nepal’s case, both views have some merit. Development is necessary. So is foresight.

The government’s target of net-zero emissions by 2045 is ambitious and, for now, largely theoretical. Achieving it will demand more than maintaining forest cover. It will mean electrifying industry, regulating transport, reforming agricultural practices and investing in clean infrastructure before the window for cost-effective change closes.

Nepal has proven that progress is possible when incentives and ingenuity meet—its forests are living proof. The real test now is whether that same alchemy can tame its factories and fuel tanks, before the country’s canopy of carbon neutrality starts to fray. ■