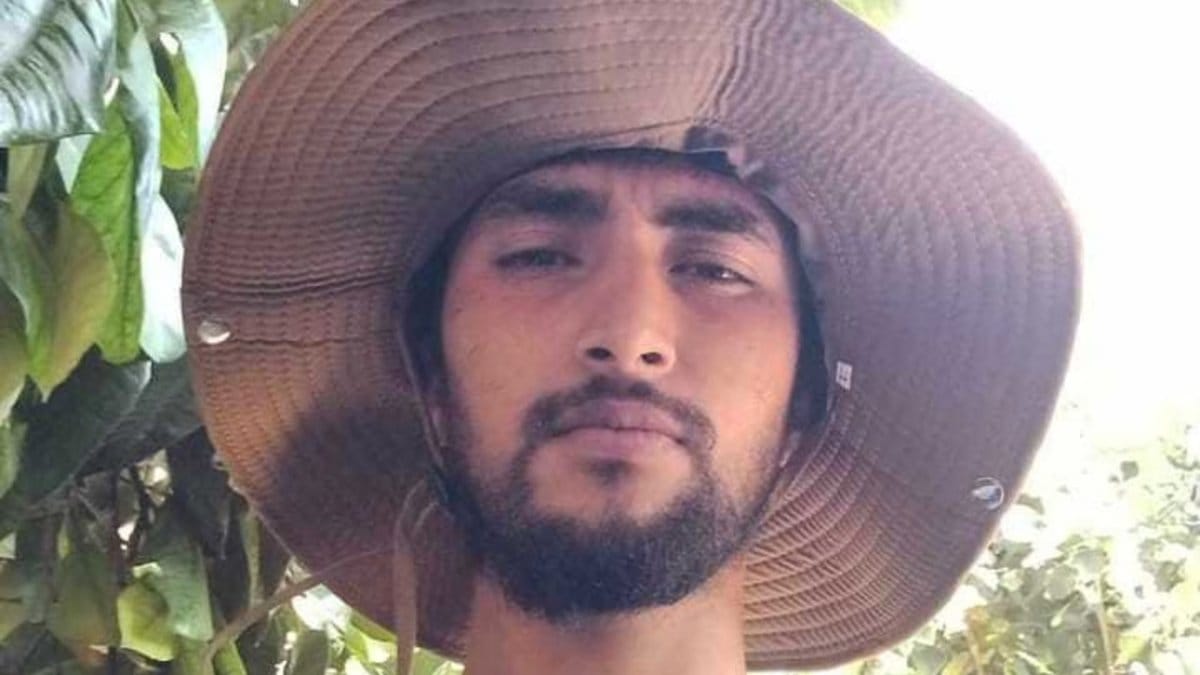

ON OCTOBER 7th 2023, Bipin Joshi, a 22-year-old Nepali student, was on a kibbutz (collective farming community) in southern Israel. He was studying under an “learn-and-earn” programme that is a popular route for young Nepalis seeking a future abroad. When Hamas attacked, it seized him in a mass kidnapping that swept up some 270 hostages from 13 countries. Ten months or so later, the Thai government had freed its 28 captives. The Philippines, the UK and America had extracted its nationals. But Mr Joshi was left in Gaza, the only foreign hostage whose fate remained unknown. This week his family was told he had been killed.

His ordeal became a national humiliation. It exposed the weakness of Nepal’s diplomatic corps as well as the complacency of its political class and the flimsiness of its global standing. It also showed the callousness of a state that depends on its migrants (the money they send home amounts to a quarter of gdp) but abandons them in their hour of need.

Mr Joshi’s fate was a test of Nepal’s diplomatic maturity. It failed. Weeks after the kidnapping, Narayan Prakash Saud, then serving as foreign minister under Pushpa Kamal Dahal’s government, reportedly asked journalists how to contact the International Committee of the Red Cross. It was an extraordinary admission of ignorance from the country’s top diplomat. While other governments mobilised intelligence assets and back-channel intermediaries, Nepal’s efforts seemed limited to press releases and polite letters. Its embassies were reduced to spectators.

Contrast that with Thailand’s approach. It secured proof-of-life videos for its citizens within a month. Diplomacy via Malaysia and Iran, which have ties to Hamas, helped negotiate their release. The Philippines leveraged its long-standing role as a source of migrant labour in Israel to extract its nationals early. Nepal’s outreach to Qatar, Turkey and Egypt produced no visible progress. Its diplomatic relationships, it turned out, were as shallow as a puddle.

The burden of activism fell to Mr Joshi’s family. His mother, Padma Joshi, and his sister did more international lobbying than Nepal’s entire foreign service. They marched through Tel Aviv, met Israel’s president, Isaac Herzog, and lobbied António Guterres, the UN secretary-general. Back in Kathmandu, the political class treated the case as an administrative nuisance. Governments changed; condolences were issued. But there was no sustained pressure.

Nepal’s then ambassador to Israel, Kanta Rijal, seemed to epitomise the helplessness. When pressed by Mr Joshi’s family, she reportedly retorted: “He is not in my pocket where I can pick and give him to you.” It was not just a failure of diplomacy, but of empathy. The state could not muster either urgency or imagination.

All this reflects deeper pathologies. Nepal’s foreign policy is largely transactional and ceremonial. Its embassies are often underfunded and staffed by political appointees rather than professional diplomats. In international forums, the country speaks the language of peacekeeping and moral solidarity—it contributes more troops to UN missions than any other country. Yet when it came to a life-and-death negotiation over one of its own, it had no influence and seat at the table.

Domestic political instability ensured no continuity of purpose. A revolving door of cabinets—there have been three prime ministers (including this caretaker government) since Mr Joshi’s kidnapping—meant that each foreign minister issued sympathy and moved on. The state was too busy fighting over ministries to fight for one of its sons.

Mr Joshi’s story is also one of migration and the broken social contract it represents. He left Nepal because he saw no future at home—a student who became a fruit-picker abroad. The elites who live off remittance-fuelled consumption showed no urgency to save the worker who embodied that system.

Mr Joshi’s remains will return home this week. His story is the moment Nepal’s global irrelevance became human and visible. A state that sends its youth abroad to survive could not bring one back—alive. ■